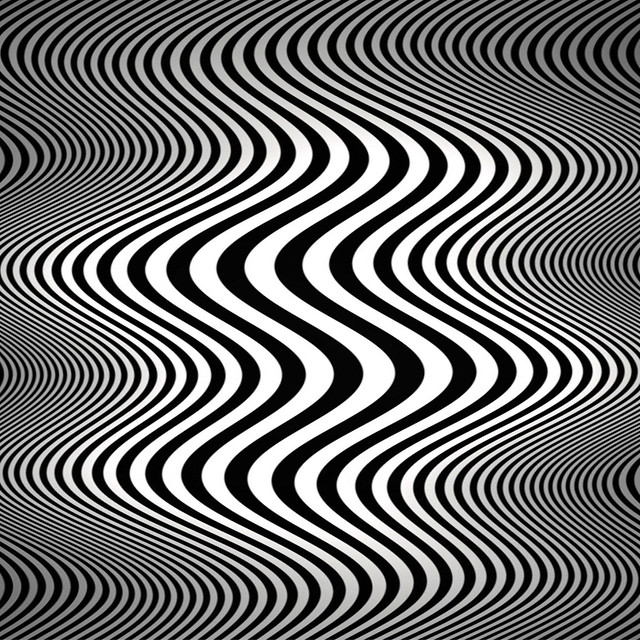

The one labeled "Ouchi Illusion" was roughly the basis of our experiment. It works on rapid movements of the eye of which we're usually unaware. This all sounds like science rather than art, but that's the great thing about the arts, they borrow inspiration from the world around them.

The artist in the picture is Bridget Riley, certainly the most well-known artist from the Op Art movement. These artists incorporated the science of optics to add an additional dimension to their abstract artwork. Below are some examples of Riley's artwork.

To create our artwork, we used white paper and permanent markers. In order to create the solid areas of black to contrast with the blank paper we had to concentrate on filling in any left-over white spots; that kind of obsessiveness required us to work on small scale, in contrast to Riley's work which was often quite large. My hope is that by displaying the artwork densely packed together we can recreate that large-scale effect in our hallways!

The key to Op Art is precise draftsmanship. We used rulers to create horizontal and vertical lines intersecting to form a grid. We mapped out our checker pattern by placing Xs in the alternating squares. We had to make two identical versions of these grids so that we could cut-out and glue the center of one (slightly askew) to the center of the other. In order to make identical grids, we used carbon paper, a material we were familiar with from our Jasper Johns projects.

One of the pieces in this group is slightly different than the rest. A student came to me having accidentally cut a circle out of the center of BOTH of his squares. This actually provided an opportunity to experiment a little more. He glued the leftover scrap from one to a piece of backing (construction paper) and then reinserted the center, turning it slightly askew. The other circle he cut down to a smaller size and glued that to the center of the bigger circle. It's possible that his mistake might become an additional step the next time I do this project!

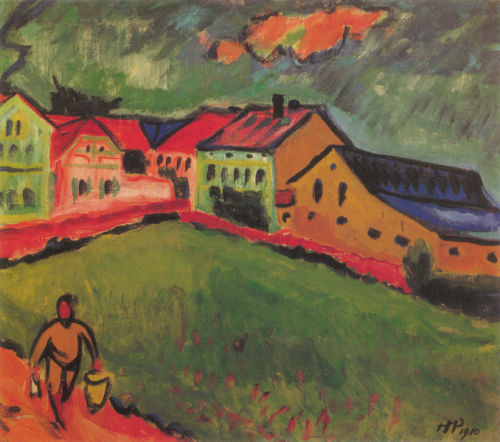

There was one odd question from a student in one of my classes. When we looked at a picture of Bridget Riley and learned her name a student asked "Why a girl?" The student was unable to elaborate exactly what he meant by the question (i.e. why NOT a girl?) but it makes me think I should put more effort into featuring more female artists. For instance, many of the examples of artwork we looked at in our German Expressionism project were by Gabriele Munter--a female artist--but we never referred to her as an individual but rather as a member of a group, and we certainly never saw a picture of her. It may be that more prominent artists in the history of Western Art have been men due to restricted access to education, but if that trend is going to be subverted into the future so that more girls grow up imaging the possibility of becoming a famous artist it's important that young children not unconsciously associate the word "artist" with a purely masculine model. Food for thought for me.